Hebrew Bible scholars have long recognized that the writer who penned the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and much other narrative in the first 5 books of the Hebrew Bible (called the Pentateuch, or Torah) had a distinctly anti-Canaanite agenda, and that his anti-Canaanite polemic started in his Eden story. Focusing on this helps us to decipher the meaning of that story, as I have stressed in my new book, The Mythology of Eden, and in talks that I’ve given on the subject at scholarly conferences.

This author, known as the Yahwist (because he was the first author of the Hebrew Bible to use the name Yahweh for God), most clearly set out his anti-Canaanite views at the beginning of his version of the Ten Commandments, in Exodus 34:12-15, where Yahweh warns the Hebrews against associating with the Canaanites, intermarrying with them, and worshipping their deities; Yahweh also orders the Hebrews to tear down Canaanite altars, pillars, and asherahs (wooden poles (stylized trees) in sanctuaries that were the cult object of their goddess Asherah (in Hebrew pronounced ah-shei-RAH) and symbolized her). Against this background, the anti-Canaanite polemic in the Eden story becomes apparent, especially that against the goddess Asherah, who at the time was widely viewed by Israelites as Yahweh’s wife or consort. As official Israelite religion trended toward monotheism, the other local deities had to be eliminated (Asherah in particular), and Yahweh appropriated their powers and functions. Insofar as this process affected Asherah, I call this “Yahweh’s Divorce,” and the proceedings began in the Yahwist’s Eden story.

Before the rise of Israel, Asherah was the wife of El, the head god of the Canaanite pantheon. According to the archeological evidence, the people who became Israelites were mostly native Canaanites who settled in the hills of what is now the West Bank, while it seems that small but influential groups also migrated there from the south in the Midian (in and around the Araba Valley in Sinai). As the Bible itself testifies, that is where Yahweh veneration appears to have originated, and, in a process that in this respect resonates with the Moses story, the migrants introduced Yahweh to the native Canaanites who were becoming Israelites. Over time, El declined and merged into Yahweh. As part of that process, Yahweh inherited Asherah from El as his wife.

The Hebrew Bible refers to Asherah directly or indirectly some 40 times, always in negative terms (so she must have been a challenge). Most references are indirect, to the asherah poles that symbolized her, but a number of them clearly enough refer directly to the goddess Asherah (e.g., Judges 3:7; 1 Kings 15:13; 1 Kings 18:19; 2 Kings 21:7; 2 Kings 23:4-7; 2 Chron. 15:16). Evidently she was part of traditional official Israelite religion, for an asherah pole even stood in front of Solomon’s Temple for most of its existence, as well as in Yahweh’s sanctuary in Samaria. There is also much extra-biblical evidence of Asherah in Israel from the time of the judges right through monarchical times, including in paintings/drawings, pendants, plaques, pottery, (possibly) clay “pillar” figurines, cult stands, and in inscriptions. Several inscriptions specifically refer to “Yahweh and his Asherah [or asherah].” (It is not entirely certain whether the goddess herself or the asherah pole symbolizing her is being referenced here, but either way ultimately the goddess is meant, and she is being linked with Yahweh.)

The Yahwist and the other biblical writers could not accept the presence of this goddess as a deity in Israel, much less as the wife of Yahweh, who they specifically depicted in non-sexual terms. So they declared war on her, in part by mentioning her existence sparingly in the Bible, by referring to her and asherahs negatively when they did mention her, and by waging a polemic against her by allusions that would have been clear to the Yahwist’s audience. These tactics are apparent in the Eden story, from the kinds of symbols used and the trajectory of the narrative. These symbols include the garden sanctuary itself, the sacred trees, the serpent, and Eve, herself a goddess figure. In ancient Near Eastern myth and iconography, sacred trees, goddesses, and serpents often form a kind of “trinity,” because they have substantially overlapping and interchangeable symbolism and are often depicted together. Let’s examine each of these symbols briefly.

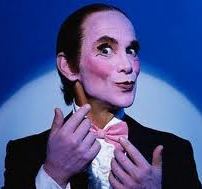

An Egyptian example of the common “trinity” of sacred tree-goddess-serpent also appearing in the Eden story. Here Nut as tree goddess nourishes the deceased and the deceased’s ba. The serpent is in its common guardian role, in an erect posture. From Nils Billing, Nut: The Goddess of Life in Text and Iconography, fig. F.3.

The Garden. Originally in the ancient Near East, the Goddess was associated with and had jurisdiction over vegetation and life, which she generated herself. People partook of the first crops (including fruit) as her bounty – indeed her body and her divinity – and set up her sanctuary with garden of crops for this purpose. Such a sacred garden sanctuary was “estate” over which she exercised jurisdiction. Examples include Siduri’s vineyard with a sacred tree in the Gilgamesh epic, Inanna’s garden precinct with sacred tree in Sumer, Calypso’s vineyard sanctuary in Homer’s Odyssey, and Hera’s Garden of the Hesperides. Garden sanctuaries of gods and kings evolved later, when religion became more patriarchal, sky gods came to dominate, and goddesses were substantially devalued. In the Eden story, Yahweh’s both creating the garden (i.e., life) and being in charge of it can be viewed as part of this process: There the Goddess (here Asherah) was eliminated from the garden sanctuary and from her functions there.

Sacred trees were thought to connect with the divine realms of both the netherworld and the heavens, and therefore were considered conduits for communicating with and experiencing the divine and themselves are charged with the divine force (thought of as “serpent power”; see below). In harmony with the seasons, trees embody the life energy and symbolize the generation, regeneration and renewal of life. Therefore, they are associated with the source of life, the Earth/Mother Goddess. Accordingly, sacred trees were venerated in Palestine in sacred sanctuaries known as “high places,” as means of accessing and experiencing divinity, principally the goddess Asherah. (Similarly, the divinity of the male deity was accessed through vertical stone pillars, e.g., the one set up by Jacob at Bethel.) In the Eden story, the two sacred trees of knowledge of good and evil and of life allude to this traditional role of sacred trees, but the meaning is turned upside down. In the story, Yahweh even creates the trees. In ordering Adam not to partake of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, by implication Yahweh was telling the audience not to venerate sacred trees in the traditional fashion. And in any event, the theretofore divine knowledge of good and evil that was acquired through eating the fruit is linked with Yahweh, not any goddess. And at the end of the story the tree of life is clearly designated as Yahweh’s, being guarded by his trademark symbols, the paired cherubim.

Serpents. In the ancient Near East, serpents had both positive and negative connotations, and in the Eden story the Yahwist played on each. In its positive aspect, the serpent represented the divine force itself, responsible for creation, life, and rebirth, as symbolized by its constant shedding of its skin. This and the fact that it lives within the earth (the netherworld) made for a natural association with the Mother Earth Goddess. As a result, the serpent was venerated as having divine powers and was used in rituals, including in marriage (to secure conception of children) and to maintain health. Serpents were also considered wise and sources of knowledge, and thus were used in divination. (The Hebrew noun for serpent (nāḥāš) connotes divination; the verb nāḥaš means to practice divination, and observe omens/signs.) Hence the serpent’s connection with transmission of the knowledge of good and evil in the Eden story. This “good” serpent was typically depicted in an upright or erect form, as in the case of the Egyptian erect cobra (in the illustration above), Moses’ bronze serpent on a pole, and the serpent on Asclepius’ staff (now the symbol of our medical profession).

But the serpent also was represented negatively as unrestrained divine power, which produces chaos, which is evil. Therefore, in creation myths the serpent/dragon represents the primordial chaos that must be overcome in order to establish the created cosmos (known as the “dragon fight” motif). This primordial chaos serpent is most often a serpent/dragon goddess (e.g., Tiamat in the Babylonian Enuma Elish) or her proxy (Typhon was the creation of Gaia). The serpent in this “evil” aspect is most often depicted horizontally. In the Eden story our author used this negative aspect, while parodying the traditional positive associations, which Yahweh appropriated. Thus, in the story, the serpent connoted chaos and symbolized the chaos in Eve’s heart as she deliberated. At the end of the story, Yahweh cursed the serpent and flattened its posture (compared with the upright/erect posture it had when talking with Eve). As a result, Yahweh was victorious over the serpent and chaos and, by implication the Goddess, in a mini version of the above-mentioned dragon fight motif.

The Goddess. As noted by numerous biblical scholars, the Goddess is also seen in the figure of Eve herself, the last figure in our trinity of tree-serpent-Goddess. In the Eden story she is given the epithet “the mother of all living,” an epithet like those given to various ancient near Eastern goddesses including Siduri, Ninti, and Mami in Mesopotamia and Asherah in Syria-Palestine. Eve’s actual name in Hebrew (ḥawwâ), besides meaning life (for which goddesses were traditionally responsible), is also likely wordplay on an old Canaanite word for serpent (ḥeva). The name of the goddess Tannit (the Phoenician version of Asherah) means “serpent lady,” and she had the epithet “Lady Ḥawat” (meaning “Lady of Life”), which is derived from the same Canaanite word as Eve’s name (ḥawwâ). At the end of the story, Eve is punished by having to give birth in pain, whereas goddesses in the ancient Near East gave birth painlessly. Further, in Genesis 4:1, Eve needs Yahweh’s help in order to become fertile and conceive, a reversal of the Goddess’ power and function. (Indeed, Eve is even created from Adam!) Adam’s only fault was “listening” to Eve in order to attain divine qualities. Here the Yahwist may be alluding to Goddess veneration, saying not to worship her. This seems to be one reason for the punishment consisting of woman’s subjugation to man in Genesis 3:16.

As a result of these events, by the end of the story Yahweh is supreme and in control of all divine powers and functions formerly in the hands of the Goddess, and Canaanite religion in general has been discredited. Yahweh is in charge of the garden (formerly the Goddess’ province), from which chaos has been removed. Sacred tree veneration has been prohibited and discredited, while Yahweh appropriates and identifies himself with the Tree of Life (see also Hosea 14:8, where Yahweh claims, “I am like an evergreen cypress, from me comes your fruit.”). The serpent has been vanquished, flattened, and deprived of divine qualities, and thus is not worthy of veneration, and enmity has been established between snakes and humans. The Goddess has been discredited, rendered powerless, and is eliminated from the picture and sent into oblivion. Yahweh’s divorce from her has been made final, at least in the author’s mind. But in fact she persisted, and her equivalents in the psyche inevitably have persisted to this day, as they must.